Imagine trying to lift a barbell, heavy television set, or a wriggling child off the ground. Now imagine trying to do it after having had your hands bound in casts for 12 hours or more each day since infancy. Sounds a lot more difficult, doesn't it? You can almost feel it slipping away through your weak hands and numb fingers.

An increasing number of coaches and podiatrists say that our feet are in this type of condition when we spend years upon years wearing supportive, cushioned footwear. This has general health implications: Shoe-wearing societies suffer from a variety of foot and ankle afflictions that are all but nonexistent in cultures where people spend most of their time barefoot. The experts I spoke with say it also has repercussions for both injury prevention and performance in athletics and weight training. The answer, they say, is to strengthen your feet.

Many shoe companies seem open to the challenge. They offer so-called "minimalist" shoes, which are usually wider, flatter, and less supportive than traditional sneakers. Vibram FiveFingers "toe shoes" are the most visible (and some argue ugliest) incarnation of this trend, while the Nike Free series is the most popular. We reviewed the latest offerings from all the major companies.

The dominant shoe in the contemporary gym is still a well-cushioned running shoe, so these upstarts need to make a strong case. Here's why you should consider kicking your protective footwear to the curb.

Stable From the Ground Up

When you lift a barbell, swing a kettlebell, or jump onto a box, it feels like you're moving a load upward, using muscles from the legs and back to fight against gravity's pull. But from another perspective, you direct force into the ground—through your feet. In a 2010 article for powerlifter Dave Tate's website EliteFTS, trainer Martin Rooney portrayed this relationship concisely, writing, "Our feet are the only part of our anatomy that touches the ground to transmit all the force that we spend so much time developing in the rest of our body."

The potential (albeit debated) benefit of having shock absorption between ground and foot is clearer if you picture a marathoner pounding away, heel-toe-heel-toe, at mile 25. But in the context of the gym, the potential downside is clearer: Force absorbed by foam is force lost. And with it goes sensation and muscular control beyond just the feet.

"The muscles in your feet tell you what to do, and then the muscles in the trunk and the hips basically do the work," says Jay Dicharry, a physical therapist and Director of the SPEED Performance Clinic and the Motion Analysis Lab at the University of Virginia. "Your feet are the first thing that hits the ground, and if they work, then things simply work well up the chain."

New York-based podiatrist Dr. Emily Splichal points out that the feet are crucial in activating the stretch reflex, an involuntary muscular contraction that enables weightlifters to blast out of the bottom of squats and heavy lifts. Without it, these lifts would be miserable, if not impossible. "You get this impact, your body takes this force, and it releases it elastically," Splichal says. "If your shoe is designed to absorb the shock, you lose that energy transfer. So you are now no longer an efficient mover. And if you're not an efficient mover, you're now muscling your way through things, and now you're at risk for overuse injuries."

Both Splichal and Dicharry frequently reference the work of the late physical therapist Vladimir Janda, whose wide-ranging research included studying how the muscles of the hips and gluteal muscles respond to either being barefoot, or wearing unstable footwear. Janda concluded that stimulating the proprioceptive response—our body's sense of balance and coordinated movement—increased gluteal and midsection activation, hip stabilization, and even had potential to help alleviate lower-back pain. In short, it makes the core and lower body work harder and become stronger. A recent study published in "Footwear Science" likewise found that the simple act of trying to balance on a single leg barefoot also elicited significantly higher muscle activity throughout the leg than doing so in shoes.

"If you are more in contact with the ground, then the intrinsic muscles [of the foot] are going to fire a little more, and they are going to become stronger," Splichal says. "There is a lot of research showing that when you stimulate the bottom of the foot, and the stabilizer [muscles] fire up, that leads to a faster lumbar-pelvic complex stabilization. So athletes feel stronger in their movements, because their base is more stable."

What's the Big Deal With Little Shoes?

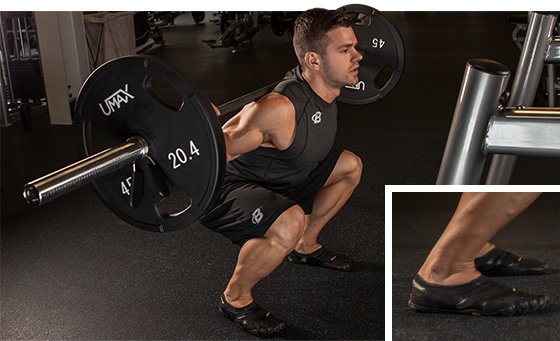

Splichal says she has worked with powerlifters who made the switch to lifting and training barefoot, with great success; they report being able to lift more weight with better form. Arnold Schwarzenegger and other golden age bodybuilders were often photographed lifting either barefoot or in flip-flops. But what about people who train in places where going barefoot isn't an option?

This is where minimalist footwear comes in. These shoes claim to come as close as possible to being barefoot, putting you more in contact with the ground, forcing your foot and lower leg to do more, and encouraging physical feedback from the ground rather than shielding you from it.

Boston-based trainer Eric Cressey is one advocate of training in minimalist shoes. He says he's seen consistently positive results in his clients, ranging from "subtle a-ha moments" to more pronounced benefits. "We've seen folks who have actually lost shoe sizes as they've gotten their fallen arches back," he says, although both he and Splichal clarify that this isn't the norm. "Additionally, I've known people whose lower leg symptoms have resolved by getting into minimalist footwear because of the improved ankle mobility and strength of the smaller muscles of the feet," he says.

Unfortunately, while there has been a number of studies in recent years looking at how these shoes impact injury rates in long-distance runners—both positively and negatively—there has been almost no research studying their effects for other types of training. One promising study published in "Footwear Science" in December 2012 looked at the effects training in minimalist shoes had in all-out athletic training like rope skipping, running stairs, and jumping, and found that subjects' toe flexor muscles were significantly strengthened over subjects who performed the same movements in traditional shoes. Increased strength in the forefoot has been shown elsewhere to improve general athletic performance, particularly jumping and sprinting.

Until more research is performed, Splichal says strength and conditioning remains a promising "next frontier" of research for barefoot and minimalist footwear. Shoe companies seem to agree; many now offer training-focused minimalist models. The appeal is clear: because strength training lacks the overwhelming injury rates of running—approximately 82 percent of runners get injured each year—training-focused footwear has the potential to change the selling point of shoes from "You'll get injured less" to "You'll perform better."

The Minimalist Difference

The "Footwear Science" study was performed in Nike Free, by far the most popular minimalist shoe on the market. The Free is different in feel and shape than most other company's minimalist models, so it's hard to draw large conclusions between one model and the next. The latest generation of minimalist offerings comes in a wide range of styles and shoe-nesses, from the glove-like Vibram FiveFingers El-X to the shoe-like New Balance MX30V2. But they share a few dominant characteristics, including:

1 Low Heel

Perhaps the most significant difference between a traditional shoe and a minimalist model is the heel. The majority of traditional athletic shoes put out by Nike, New Balance, Adidas, and other major manufacturers feature heels that are at least 10 mm higher than the forefoot. This difference is known as the "heel drop." By contrast, New Balance's Minimus line of shoes all measure between 4 mm and flat (or "zero-dropped"), and the Nike Free 3.0 has a 3 mm drop. Some new companies such as Altra, Skora, and Vivobarefoot produce only zero-dropped shoes.

So which is the right choice? Some purists will only consider a zero-dropped shoe, but the experts with whom I spoke indicated the biomechanical differences between these heel heights is minimal for most users. "If you have a really high arch or a structurally tight Achilles tendon, that millimeter could mean something," Splichal says. "In that case, I might direct a person [to 4 mm]. Otherwise, they're all pretty much equal. Go off your own comfort."

Dicharry, who advises several shoe companies on design, says the jury is still out on precisely what small differences in heel heights mean, so thinking in terms of high-heel vs. low-heel is sufficient for the moment. "The industry is trying to look around right now and find out what height is best, and that question is unanswered," he says.

2 Firmness and Lack of Cushioning

Minimalist shoes run the gamut in firmness, and some running-focused models with low heels are still relatively cushy. But the new generation of training-focused minimalist shoes generally either has a firm feel, or feels thin enough that the ground is the dominant sensation. Dicharry says this has both safety and performance implications.

"If you are lifting and have a bunch of weight stacked on your shoulders, you would definitely want a firmer shoe, because you want to make sure that the weight doesn't collapse the shoe inappropriately," he says. Mel Siff and Yuri Verkhoshansky raised this concern in their training manual "Supertraining," going so far as to provide a list of movements incompatible with "shock-absorbing shoes," including, "squats, cleans, deadlifts, standing press, good mornings, snatches, pulls, and other standing exercises."

Even if you're devoted to your cushy cross-trainers for cardio, there seems to be no benefit to wearing traditional footwear in types of complex free-weight exercises where balance and proper form are paramount. If they're part of your program, it could be time to consider a firmer ride.

"When your foot is on a soft, unstable surface, it delays the message your foot gets from the ground," Dicharry says. "When you put your foot on firm surfaces, it just works better."

3 Wide Forefoot

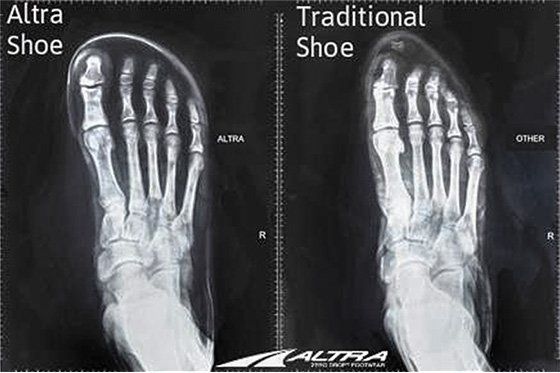

If you've been in traditional shoes for most of your life, a pair of minimalist shoes like the Altra Samson will likely feel and look like "boats," to use my father's words—in other words, very wide. This is no coincidence. The front or "toe box" of a minimalist shoe allows the digits to spread out, similar to how your toes spread when you stand barefoot on the kitchen floor.

This is where the new generation of minimalist footwear most greatly differs from the likes of Chuck Taylors, Adidas Sambas, and other lightweight retro-trainers, which tend to taper to a point. You may feel at first like you're swimming in them, but over time, it's likely that your foot will expand to some degree, and you may have trouble cramming your feet into a narrow, tapered sneaker ever again.

This is doubly the case with high heels, Splichal says. "There are [women] who are not going to stop wearing heels but can still benefit from strengthening their feet," she says. "Others realize all the pain they have been putting their feet through, and they're like, 'I can't go back.'"

4 Lightweight

As a rule, the lack of support and cushioning means minimalist trainers weigh less than traditional built-up sneakers. Cressey says this lightness is the dominant sensation that many athletes report when starting to train in them. "[They] comment on just how light on their feet they feel," he says. "When they go back to a traditional shoe, it feels like they're wearing cement blocks and not quite as in contact with the ground. I also like the versatility they provide. You can sprint, jump, lift, and change direction in them."

5 Flexibility and Lack of Arch Support

Many popular minimalist models are flexible enough to be rolled up into a ball. This is by no means universal, however, and the technology behind some shoes' flexibility can have drawbacks. Cressey says he often finds pieces of tread from flexible shoes such as Nike Frees lying around his gym after intense sled-pushing workouts, which is one reason why he favors New Balance's more solid and shoe-like MX20V3.

Similarly, minimalist shoes run the gamut when it comes to arch support. Some have just a hint, others are totally flat, and a few have arches on par with more traditional footwear. Our reviews of minimalist shoes outline which is which.

Making the Switch

There are two pieces of advice that are consistent among trainers and researchers who advocate minimalist footwear or barefoot training. First and foremost, make your choice based on fit, feel, and comfort. That means trying shoes on.

"When you are on a traditional cushioned shoe, it's like you have a marshmallow under your foot, so you can kind of collapse in there," Dicharry says. "But going toward minimal, there is less stuff under your foot, so proper fit is critical. The shape of how the shoe is constructed is one of the most important variables, and everyone has a different-shaped foot." He says he is currently working on a project attempting to determine "objective ways to match footwear to the runner," but for the strength-training enthusiast, judging by subjective fit is still best.

Everyone I spoke with also advised that anyone considering the transition must do so slowly and systematically. They can provide ample anecdotes about people who don't—"the lunatics who hop in a minimalist sneaker, immediately start running 10 miles per day on pavement, and then blame the shoes" in Cressey's words.

"Our bodies have become dependent on those soft, overly cushioned shoes, and we have gotten weak feet," Dicharry says. "So to be able to get into firmer shoes, or 'less' shoe, you need to actually improve some aspects of your body." In Dicharry's book "Anatomy for Runners," he advocates lots of single-foot balancing, jumping, and "toe yoga" exercises to strengthen feet. Foot-strengthening exercises like picking up towels off the floor are also common recommendations for people looking to strengthen their feet.

Goblet Squat

Splichal likewise insists that simply changing footwear and continuing your training apace puts you at risk for pain and discomfort. "You can't just wear the shoes," she says. "You still have to do specific exercises to strengthen the foot." She advocates going barefoot when possible and exposing the feet to a range of textures and surfaces in order to stimulate the nerves on the soles of the feet. Splichal also created a barefoot warm-up routine to help strengthen feet and activate muscles for both minimalist shoe wearers and athletes who wear other types of footwear.

Nevertheless, some pain may be inevitable. I found it took a week or so of fairly intense calf and Achilles pain (and limping down staircases) before my lower legs felt adapted to the new demands placed by minimalist shoes. So take it slowly and don't expect to become a barefoot warrior overnight. This is a project with benefits, whatever they may be, which are only going to be felt in the medium to long term.